Texas Railroad History - Tower 154 - Angleton

A Crossing of the St. Louis, Brownsville & Mexico

Railway and

the Houston & Brazos Valley Railway

Above Left: John W. Barriger

III snapped this photo of the Missouri Pacific (MP) depot in Angleton from the

rear platform of his business car as his train proceeded south toward

Brownsville on the St. Louis, Brownsville & Mexico (SLB&M) Railway.

Geographically, the view is to the northeast with the Houston & Brazos Valley

(H&BV) Railway crossing the SLB&M adjacent to the depot. By this date, probably

mid-1930s, MP owned both railroads and had erected a union depot near the

crossing. Since 1929, this crossing had been controlled by Tower 154, a

mechanical interlocking plant housed

inside the depot (or temporarily in a trackside hut if the interlocker

installation preceded

the depot being erected.) Above Right:

This undated photo from the collection of Jim Williams shows the MP depot more

clearly with the H&BV tracks passing beside it. The white placards (inset

upper right) under the corner eaves visible to

train crews on both lines announce that the controls for the Tower 154

interlocker are located

inside.

The town of Velasco was founded in 1831 along the banks

of the Brazos River four miles from the Gulf of Mexico. It was an important

town in Texas history -- the site where the

Treaties of Velasco

were signed in 1836, and a temporary capital of the Republic of Texas. The town

declined substantially after the Civil War, but by the early 1890s, economic

revival brought new construction in an attempt to create a deep water port

at the mouth of the Brazos River. Sixteen miles northwest of Velasco,

land promoters founded the town of Angleton just as investors had begun to

contemplate building a railroad -- the Velasco Terminal Railway (VTR)

-- to serve the port from a planned rail connection with the International &

Great Northern (I&GN) Railroad. The I&GN tracks were four miles northwest

of Angleton, so the land promoters offered an interest in their property in exchange for

the VTR routing their line through the center of town (reportedly, they also named the town after a VTR executive's wife.) In July,

1891, the VTR was

formally chartered with grand ideas of building all the way to Hempstead where

the VTR could connect with Houston & Texas Central (H&TC) Railway lines to

both Austin and Denison.

By the end of 1892, a 20-mile line had been completed from Velasco through

Angleton to the I&GN connection at what the railroads called Chenango

Junction, where the town of Anchor quickly arose.

The VTR went into bankruptcy in 1899, and a subsequent iteration, the

Velasco, Brazos & Northern Railroad, did likewise in 1906. It was

reconstituted again (with greater success) in 1907 as the Houston & Brazos Valley (H&BV) Railway.

The VTR had attracted the attention of E. H. Cunningham who owned a large sugar

plantation at Sugar Land. Through the Port of

Galveston,

Cunningham was importing substantial volumes of sugar cane and low grade sugar

products from Cuba that were shipped out of the port by rail and delivered to his sugar mills and refinery

by Southern Pacific (SP.) Routing through the Port of

Velasco was an intriguing option because it was closer than

Galveston and was connected by rail to Anchor, only 32 miles from

Sugar Land. Cunningham knew the I&GN and VTR could provide the necessary rail

service from Velasco, but he was

also pondering the alternative of having his own rail line from Sugar Land to Anchor,

eliminating the I&GN haul. In the 1907 timeframe, Cunningham's plantation

and sugar business was acquired by William Eldridge, who proceeded to build such a line in 1916 as an

extension of his Sugar Land

Railway (SLRy.)

|

Left: In this

1930 aerial image ((c) historicaerials.com) showing the junction at

Anchor, the I&GN line runs diagonally across the image on a straight NNE

/ SSW heading. The SLRy line to Sugar Land is visible proceeding

northwest from the junction. The H&BV line runs southeast from Anchor to

Angleton. An active connecting track is visible south of the junction

allowing movements between Angleton (H&BV) and East Columbia (I&GN).

Under magnification, a similar U-shaped connector north of the junction

can be seen that was previously in place (but no longer active in 1930) between

the SLRy and the I&GN tracks. Since those railroads had a much shorter

connection farther north between Hawdon and House Jct., perhaps it had

served as a temporary bypass during track reconstruction on the Hawdon connector.

Having reached Anchor, Eldridge

pondered building his own line into Angleton, but did not do so, opting to

interchange with the H&BV. Angleton had a rail connection to

Brownsville on the St. Louis, Brownsville & Mexico (SLB&M) Railway

offering a means of importing Mexican sugar cane. The SLB&M had built

through Angleton a decade earlier, the first of the Gulf Coast Lines

(GCL) network established by B. F. Yoakum. Yoakum was a major force in Midwest

railroading -- simultaneously Chairman of the St. Louis & San Francisco ("Frisco") Railway,

a member of the Colorado & Southern Railway Board of

Directors, and Chairman of the Executive Committee

of the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad, effectively its

CEO. Yoakum was also a native Texan who knew Texas railroading

very well. His plan for the GCL was to compete with SP along

the Gulf Coast by purchasing railroads (or building new ones) that he could

stitch together into a continuous route from Brownsville to New Orleans centered

at Houston.

The SLB&M had succeeded in building south

from Robstown to Brownsville in 1904. This gave the Lower Rio Grande Valley its first access to

the national rail network through a Robstown connection to the Texas Mexican

("TexMex") Railway, which served both

Corpus Christi and Alice. From both of those towns, the

San Antonio & Aransas Pass

(SA&AP) Railway (where Yoakum had first become a rail executive) provided service north to

San

Antonio and Houston. Yoakum proceeded to build north from Robstown,

but rather than go all the way into Houston,

he stopped at

Algoa and negotiated trackage

rights from there to Houston on rails of the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe

(GC&SF) Railway. Its main line out of

Galveston passed through Algoa and it had a branch line into Houston

from Alvin, five miles west of Algoa. |

Alvin Sun, May 26,

1905 |

Drainage infrastructure had

long been a public policy issue in Brazoria County, but Yoakum had not

anticipated the difficulty of building through the Brazos river

bottomlands. To maintain schedule, Yoakum built southwest from Algoa

through Angleton to the Brazos while continuing to build east from

Bay

City to the river.

Left:

This newspaper article updated

the "Coast line" (GCL) progress south from Algoa through

Liverpool, anticipating that

grading would be complete to the river within 90 days.

Right: Seven months

later, the Brownsville Daily Herald of

December 5, 1905 reported that ties had been laid from Angleton to

Oyster Creek, less than half the distance to the Brazos. Yet, the

railroad was claiming "through trains" by January 1, 1906, only three

weeks away! The first passenger train to make the trip through the

Brazos bottomlands and across the river bridge was a VIP train from

Brownsville to Galveston on March 13, 1906. Regular service

could not commence because the grade, ballast and bridges were

determined to be insufficiently engineered to withstand the rainy season

in Brazoria County. Regular service between Bay City and Algoa finally

began in the summer of 1907, more than a year later. |

|

Below: Yoakum's engineers

did an excellent job designing a swing bridge for the Brazos River that allowed

river traffic to pass. The bridge opened in 1907 and remains in service for

Union Pacific. It is no longer required to open for river traffic. (Google

Street View, May, 2024)

Yoakum had structured the ownership of the GCL

railroads through multiple syndicates operated by the St. Louis Trust Co.;

individually, the railroads were managed at a high level by Frisco executives.

The Frisco bought the GCL railroads outright in 1910 -- they were profitable,

and Frisco leadership surely expected improved traffic flow between the Gulf

Coast and Midwest under direct management control. When the Frisco's financials

declined in 1914, it entered receivership, taking the GCL railroads with it. The

bankruptcy judge separated the GCL railroads from the Frisco and established a

new, independent corporate parent, the New Orleans, Texas & Mexico (NOT&M)

Railway, through which all of the GCL railroads were owned. The NOT&M

had been

one of the GCL railroads, but it was re-chartered for the purpose of also becoming

the GCL parent company.

When the I&GN came

out of yet another receivership in 1922 as a new corporation (dropping the

"and" to become simply "I-GN") it owned more than 1,100 miles of track

in Texas, but its repeated financial reorganizations made it a good target for

takeover. The Frisco tried to buy it in 1922 but the sale was nixed by the Interstate

Commerce Commission (ICC.) The Missouri Pacific

(MP) Railroad tried to buy the I-GN in 1924 as a means of gaining access to the Texas

market, but again, the ICC denied approval. MP's

fallback strategy was to arrange for the NOT&M to buy the

I-GN, simply to keep it out of the hands of other competitors. The sale of the

I-GN to the NOT&M was approved by the ICC in June, 1924. MP was then

approved to buy the NOT&M on January 1, 1925, acquiring the

target I-GN along with all of the GCL railroads.

The other railroad in Angleton, the H&BV, was going through its own

significant ownership changes in this same timeframe. The H&BV had been able to

sustain a profitable business shipping sulfur from one of the world's largest

sulfur mines located at the town of Freeport. Freeport was a company town

founded in 1912 by the Freeport Sulphur Co. downriver from Velasco (which was

absorbed into Freeport's city limits in 1957.) The H&BV had become half-owned

by the Missouri, Kansas & Texas ("Katy") Railroad in 1913,

with Freeport sulfur mining interests owning the other half. The Katy went into

receivership in 1915, and the Katy's share of the H&BV was sold to SP when the

Katy was reorganized in 1923. As the H&BV was not connected to any other SP

railroad, SP sold its interest to the NOT&M in 1924. The NOT&M also acquired the

terminal railroad at Freeport and a branch line to a large sulfur mine at

Hoskins Mound. At Angleton, both railroads were now owned by the NOT&M, which

soon transitioned to MP ownership. The SLB&M and H&BV continued to operate

under their own names until 1956 when

they were fully merged into MP.

The H&BV / SLB&M crossing at Angleton was

uncontrolled, hence all trains were required to stop before proceeding across

the diamond. The crossing had existed since 1906, but it remained uncontrolled until

July 22, 1929 when the Railroad Commission of Texas (RCT) authorized a 10-function mechanical cabin interlocker,

Tower 154, to begin operations at Angleton. It is unclear whether the MP depot

at the crossing had been erected by the time the interlocker was installed. If

not, a temporary cabin housed the controls until the depot was built. The

interlocking plant and its controls were ultimately housed in the depot, which

bore white placards with the number "154" on the two sides of the building

visible to train crews (see photo at top of page.) Tower 154 was one of ten

interlocking plants involving the SLB&M to be commissioned in the thirteen months between September 10, 1928 and October

1, 1929, but whether this flurry of interlocker construction

by MP was performed in response to an order from RCT is undetermined. The first was a manned tower, Tower 138 in

Harlingen; the other nine were cabin interlockers at Angleton,

Allenhurst, Blessing,

Placedo, Edinburg, Alsonia, Edcouch, Lantana

and Rosita.

|

|

Left: This item from a 1949

article in Railway Age

describes a new

Centralized Traffic Control (CTC) machine "located in an office at Angleton...",

most likely the MP depot.

CTC control extended from Algoa to Vanderbilt, a town on the SLB&M about 80

rail miles south of Angleton. The article notes that the CTC machine

incorporated functions to replace the mechanical interlocker at

Angleton. |

In the years prior to when RCT began allowing automatic

interlockers (1930), cabin interlockers were used at locations where a manned tower

would not be cost-effective. The most

common application was where a lightly used branch line crossed a main line. In

such cases, the staffing expense of a manned tower could not be justified since

the signals were almost always set to allow unrestricted movement on the main

line, i.e. there was little for an operator to do. The interlocking plant and

its controls would be housed in a trackside "cabin" (a small hut

with a lockable door, e.g. Tower 152.) Trains on the lightly used line would always stop at the

crossing so that a crewmember could enter

the cabin to set the controls to produce a STOP signal on the busier line. Once

the interlocker granted a PROCEED signal, the crewmember's train would continue

across the diamond and he would

return the controls to the normal position, leaving PROCEED

signals displayed on the

busier line. If a depot was located near a crossing suitable for a cabin

interlocking, it

made sense to house the equipment and controls in the depot. In such cases, depot personnel

were sometimes certified to operate the interlocker during daytime hours so that a crewmember did not need to disembark

his train.

The ten

functions of the Tower 154 interlocker were most likely a derail in all four

directions, a home signal in all four directions and a distant signal on the

SLB&M tracks in both directions. Distant signals told approaching SLB&M trains

whether the crossing was occupied and they were located far enough from the diamond to

allow time for the train to stop. Distant signals were not needed on the

H&BV tracks -- a fixed warning sign was adequate -- because every

H&BV train stopped at the crossing so that a crewmember (or perhaps depot

personnel) could operate the interlocker to establish a PROCEED signal.

|

Left: map of railroads near Angleton as of 1926 (not all tracks are shown.)

The I-GN line began as the Houston Tap & Brazoria

Railway, one of the early railroads in Texas. "The Tap" ran from downtown Houston

to the east bank of the Brazos River at East Columbia, arriving

there in 1860 and earning the nickname "Columbia Tap". Its plan to

bridge the river was thwarted by

the outbreak of the Civil War; it never crossed the river. The Tap

had a reliable business hauling people, materials and products for the

sugar refineries and plantations in the area. It was acquired by the Houston & Great Northern (H&GN) in

1873, a few months prior to the H&GN's merger with the International

Railroad to create the I&GN (changed to I-GN in 1922.) In 1893, the

I&GN built a spur west from Hawdon to serve a sugar mill at House on the

plantation of T. W. House. The west end of the spur became known as

House Jct. in later years when the SLRy line from Sugar Land was built.

The GC&SF

main line out of Galveston crossed the I&GN at Arcola

in 1877 and bridged the Brazos into Richmond in

1879. E. H. Cunningham's sugar refinery at Sugar Land

was only served by SP, so he chartered the Sugar Land

Railway (SLRy) in 1893 to create competition by building south to the GC&SF and I&GN lines near

Arcola.

Between Arcola and the Brazos River,

Sugar Land Jct. did not exist until 1911

when the SLRy line was extended south to House Jct. It was subsequently

continued south to Anchor in hopes of reducing transportation costs by

routing sugar cane imports through Velasco instead of Galveston. Cane

imports from Mexico via the SLB&M at Angleton also became an option.

In 1924, the NOT&M bought the H&BV -- this was around the same time

that a branch line to a major sulfur mine at Hoskins was being built. At

the behest of MP, the NOT&M also bought the I-GN which MP had

been legally unable to acquire. MP then purchased the NOT&M in 1925,

adding the I-GN, H&BV, SLB&M and the other GCL railroads to its

portfolio. MP bought the SLRy in 1926. The I-GN line from Anchor to Hawdon

was superior to the SLRy line from Anchor to House Jct.,

so the SLRy tracks south of House Jct. were abandoned in 1932. MP

abandoned the branch to Hoskins beginning in 1970.

During MP's reorganization in 1956,

its subsidiaries became fully integrated and no longer

operated under their original names. MP's Columbia Tap branch was

abandoned in stages: south of Anchor in 1956, south of Rosharon in 1962,

south of Hawdon in 1987, and south of Arcola in 1999.

MP abandoned the former H&BV tracks from Angleton to

Anchor in 1962. They no longer served any purpose since the SLRy tracks at Anchor

were already gone and the I-GN was being abandoned between Anchor and

Rosharon. By then, Freeport shipping was being routed

exclusively on MP's former SLB&M line via Algoa and trackage rights on the

GC&SF from there into Houston via Alvin. |

Union Pacific (UP) acquired MP in 1982 and operated it

as a subsidiary until it was fully merged in 1997. The GC&SF became part of the

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway in 1887, but was not fully merged until

1965. Santa Fe merged with Burlington Northern in

1995 to create Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF.) UP still operates the rights

between Houston and Algoa via Alvin that were negotiated by Yoakum. The tracks

on the above map that remain operational are the

GC&SF (now BNSF), UP's former SLB&M line south

of Algoa, UP's former H&BV branch from Angleton to

Freeport (not including the branch to Hoskins) and UP's Columbia Tap tracks

north of Arcola. As a result of the UP / SP merger in 1996, BNSF gained trackage

rights on UP's former SLB&M line.

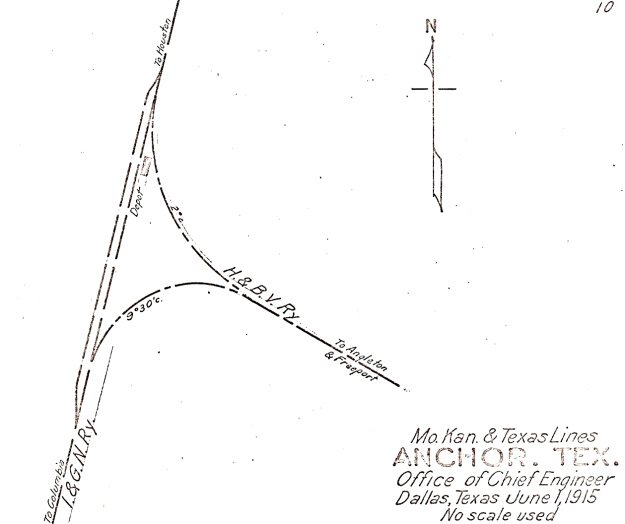

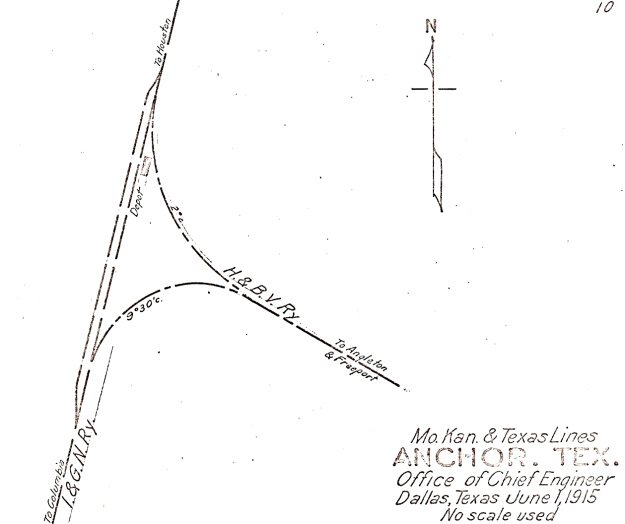

Above: These track charts

(courtesy Ed Chambers) were produced in 1915 by the Katy Railroad's Texas-based

engineering department which maintained such charts for many of the

junctions in Texas, regardless of whether Katy tracks were

present. The significant feature of the Angleton chart is

that it shows two depots, neither of which is particularly close to the

crossing. At some point, a combined MP depot for both railroads was

built near the crossing. The Anchor chart does not show the SLRy because

the drawing was produced a year prior to the arrival of the SLRy. Anchor

thrived prior to WWI, but lost its post office in 1920.

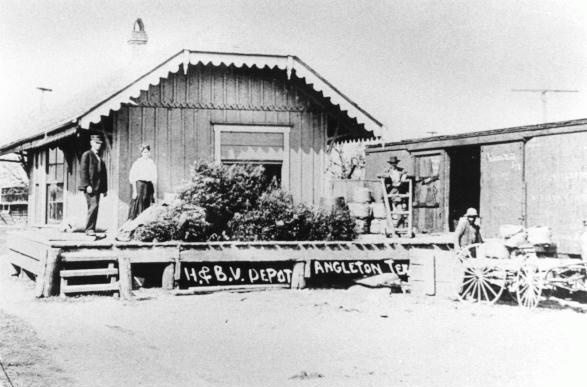

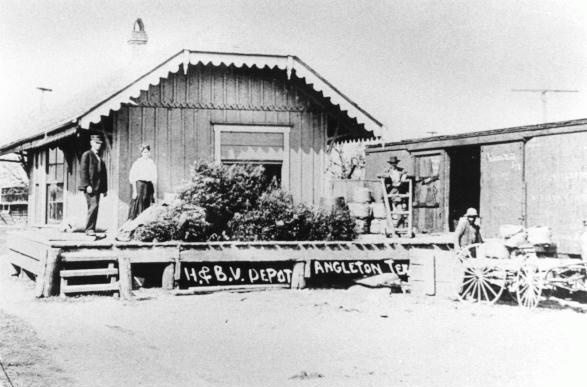

Above: These undated photos of the SLB&M (left) and H&BV

(right) depots at Angleton likely show the structures that were present at the time the Katy

track chart above was created. (Brazos County Historical Museum images)

Above Left: This Google Earth image

from 2018 shows the remaining tracks near the Tower 154 crossing, now called Angleton

Junction. The former

SLB&M crosses the image diagonally, showing the tail end of a northbound UP

train heading for Algoa. The former H&BV tracks only head south now; they

previously continued north across the SLB&M toward Anchor. Angleton Yard just

beyond the left edge of the image dates back to at least the early

1980s. It was expanded significantly in 2018 to add a Storage In Transit

yard with a capacity of 1,100 cars. The substantial rail infrastructure in this

region is due to the petrochemical plants nearby and the Port of

Freeport, which handles more than 30 million tons of freight annually. Note also

the two white "temporary buildings" adjacent to the former crossing which

replaced... Above Right:

...a former MP depot that was in use as a UP office in 2006. (Jim King photo, 2006)

Above Left:

Looking generally west, a BNSF train with Canadian National #2550 as the

trailing engine passes through Angleton heading southwest toward Bay City,

exercising BNSF rights to use UP's former SLB&M route. The track in the foreground is the southeast connector to the

Freeport line to the south (left edge of the image). Hopper cars on the

southwest connector in the distance are being pulled by a UP train into Angleton

Yard. (Jim King photo, 2006) Above Right: Looking south from the north side of

the former Tower 154 crossing, the sign sits on the former H&BV right-of-way

to Anchor. The two permanently installed "temporary buildings" in the background

replaced the former depot. (Google Street View, April 2024)

Above: These two Google Street Views of UP's former SLB&M line

were

taken from the Loop 274 overpass beside Angleton Junction facing southwest (left)

and northeast (right.)