Texas Railroad History - Towers 96, 97 and 98 -

the Galveston Island Causeway

Three Interlockers

Along the Galveston Island Causeway

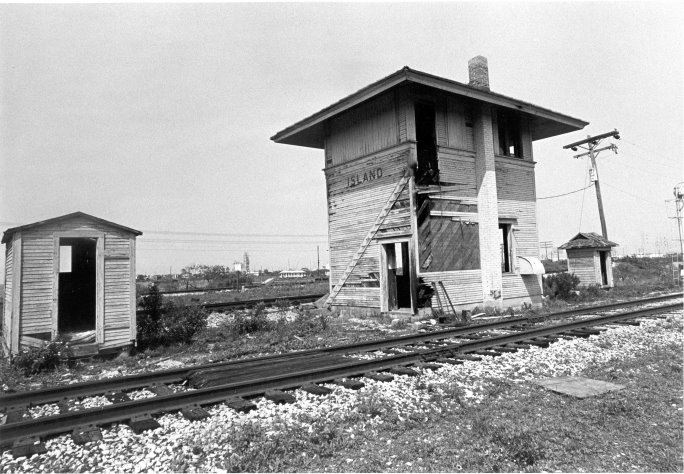

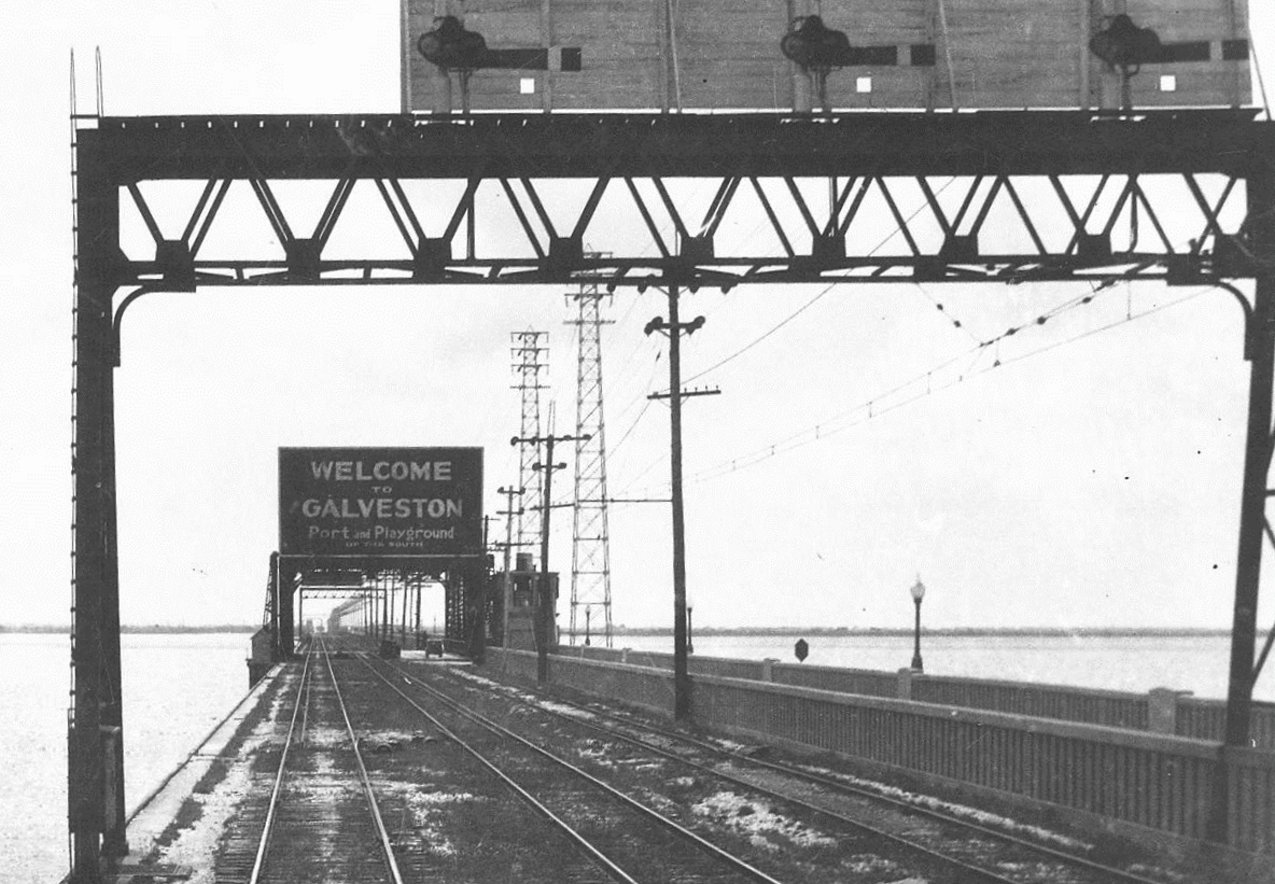

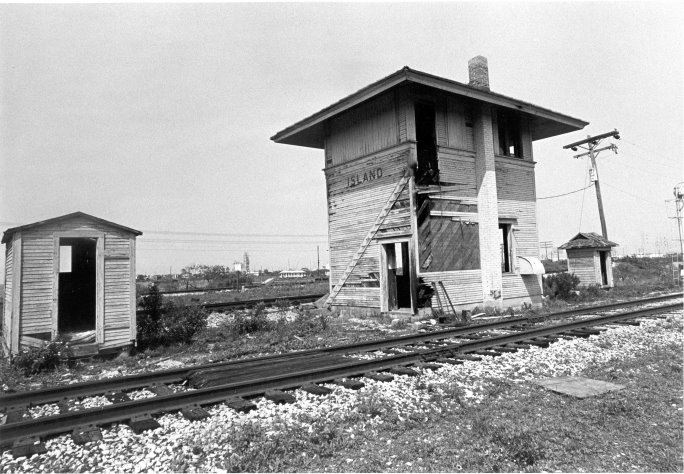

Above: Railroad executive John

W. Barriger III was northbound from Galveston Island when he snapped this

photo from the rear platform of his private railcar, most likely in the mid

1930s. His camera impulse was spurred by Tower 96, the "Island" side

interlocking tower for the Galveston Island Causeway. Barriger is looking

southeast toward Galveston as his train has just left dry land and ventured onto the

causeway for the trip to the mainland. Barriger's train is on one of the two

"steam railroad" tracks on the causeway; the other is the

track to his immediate right. Both were shared by the steam railroads serving

Galveston: the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railway, the Texas & New Orleans (T&NO)

Railroad owned by Southern Pacific, and the Galveston, Houston & Henderson (GH&H)

Railroad. The GH&H was owned by the Missouri - Kansas - Texas (MKT) Railroad but its

tracks were shared with the International - Great Northern (I-GN) Railroad. The two tracks

farther to the right are a main track and

a short passing track of the interurban Galveston Houston Electric (GHE) Railway;

note its electrified catenary.

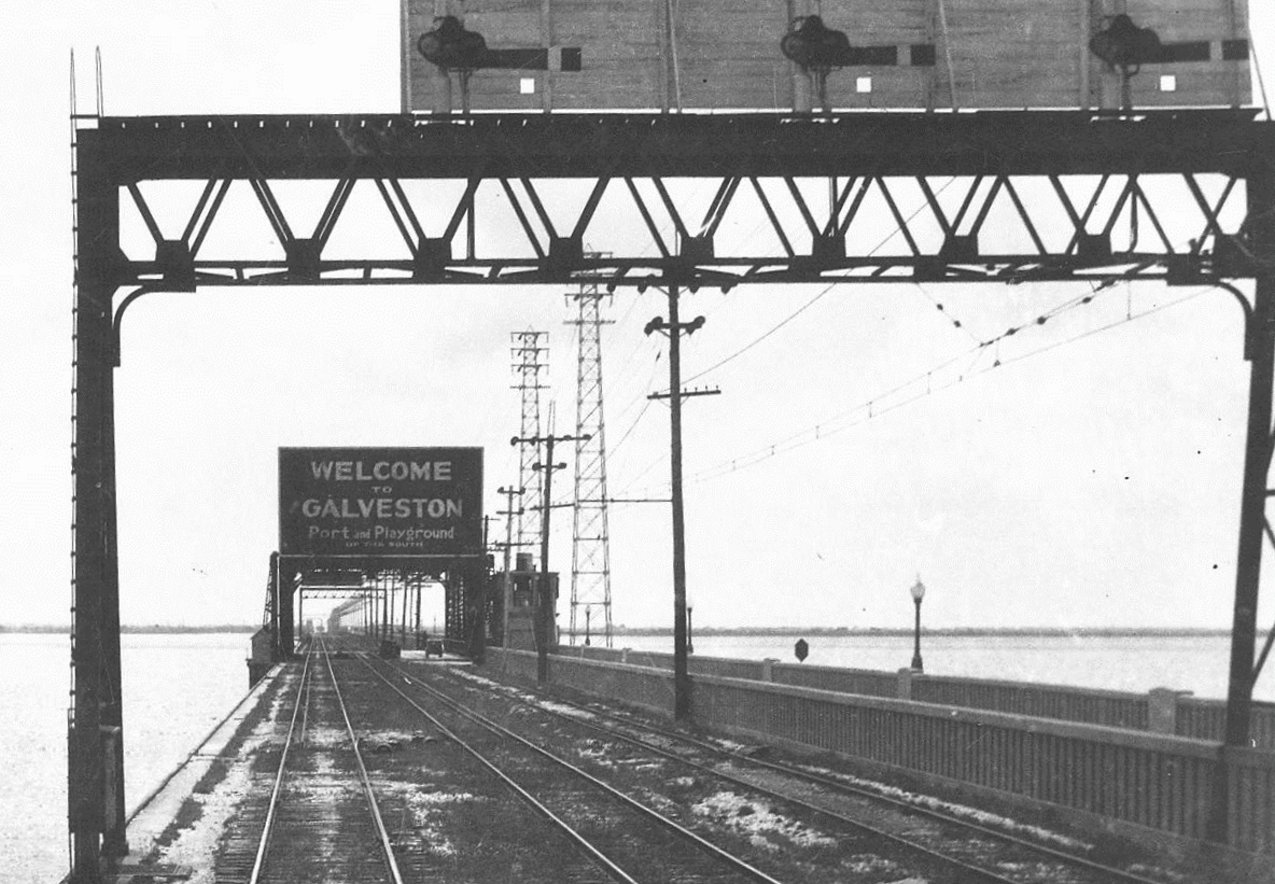

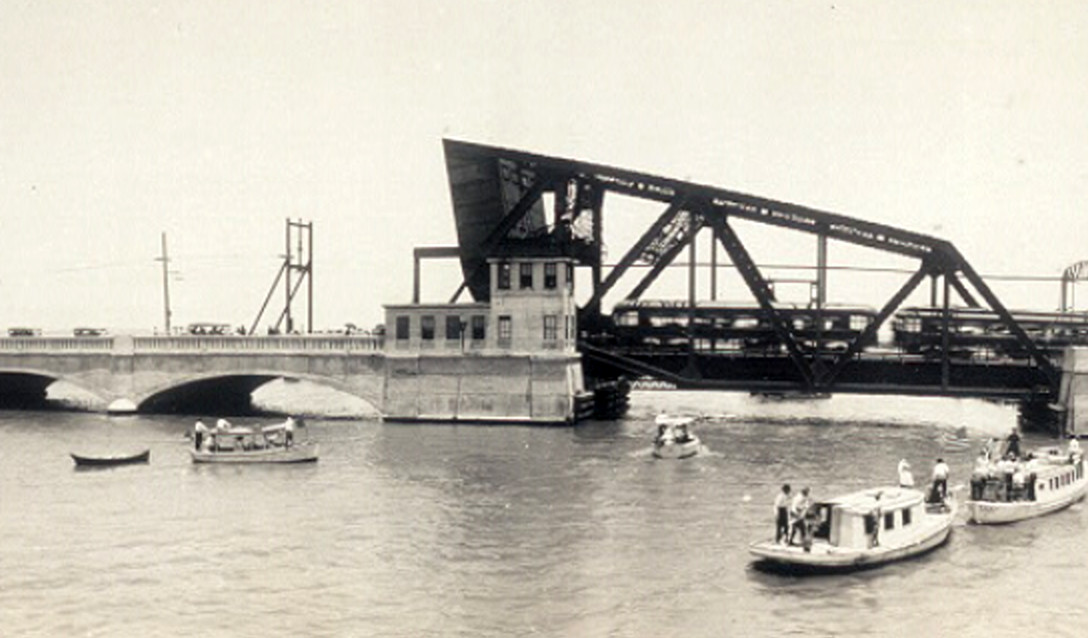

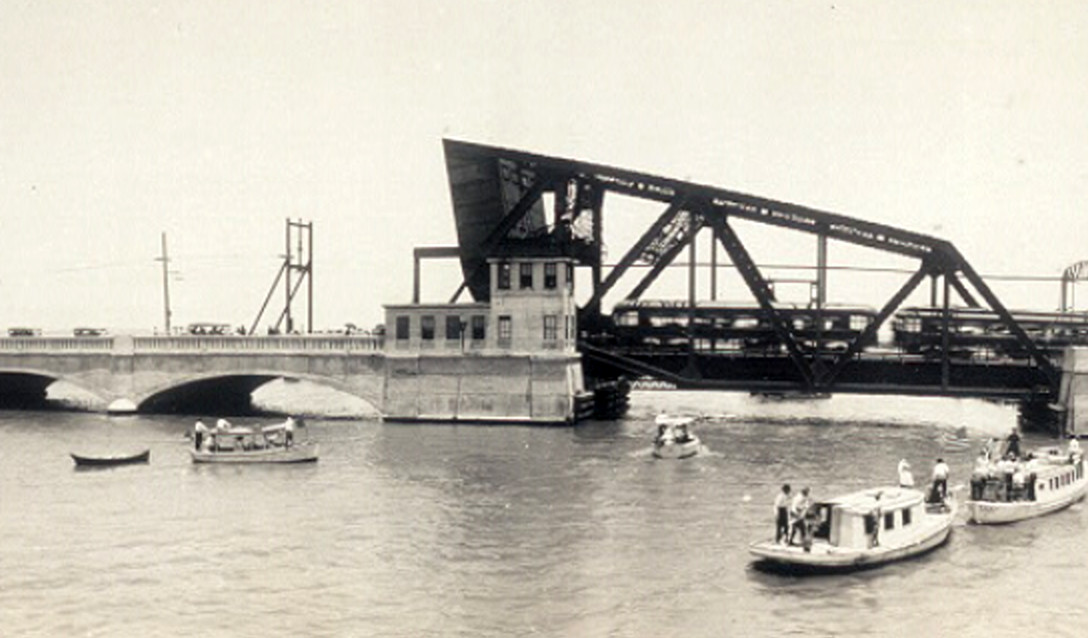

Below: Having just passed over the railroad bridge at the

center of the causeway, Barriger's camera impulse is triggered by Tower 97, the interlocking tower to

the right of the "Welcome" sign. Tower 97 controlled

the raising and lowering of the drawbridge, de-conflicting railroad and maritime

traffic. The

causeway's vehicle roadway is behind the barrier wall to the right; the automobile

visible on the GHE tracks is "driving around" Tower 97. (photos courtesy John W. Barriger III National Railroad

Library)

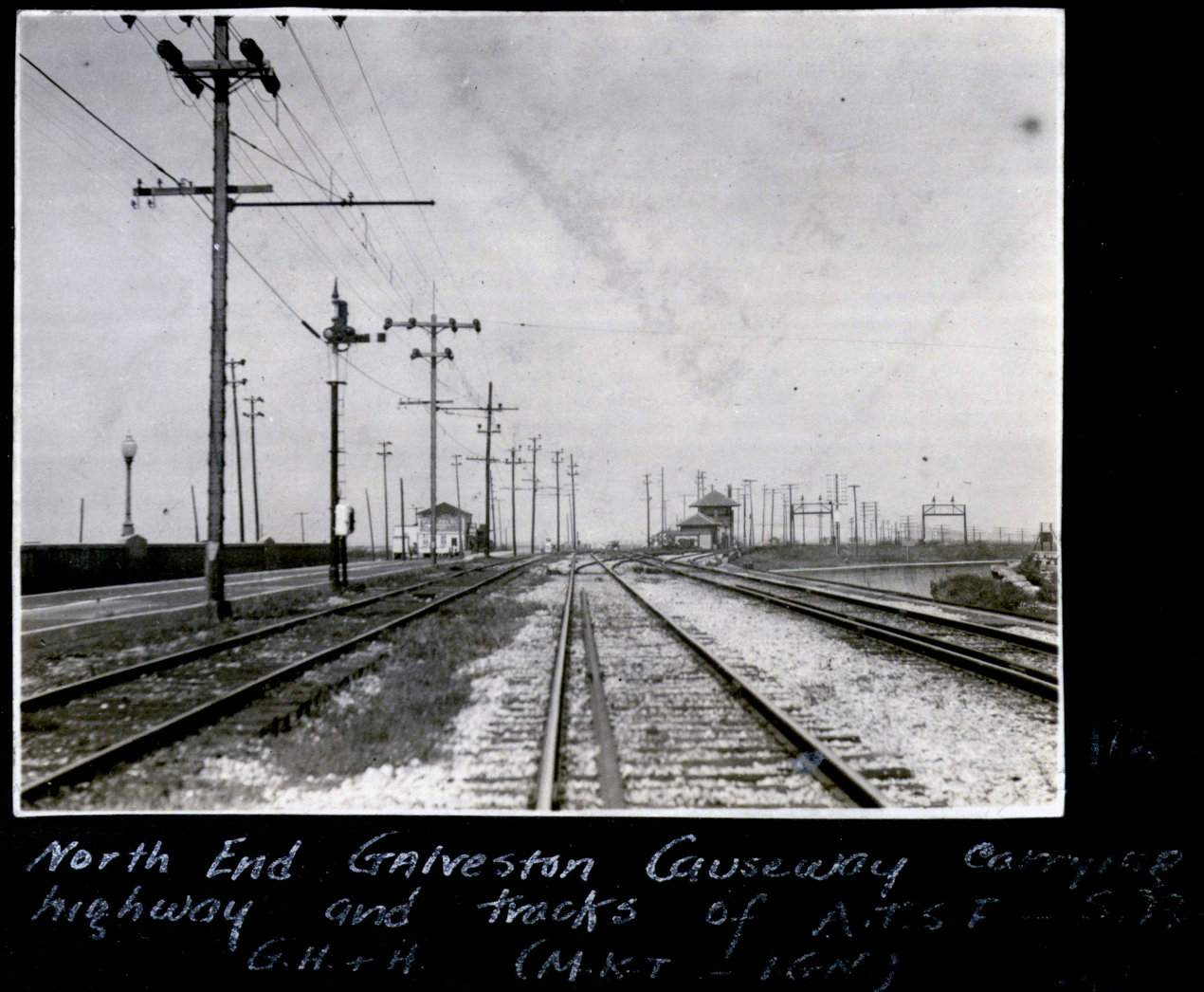

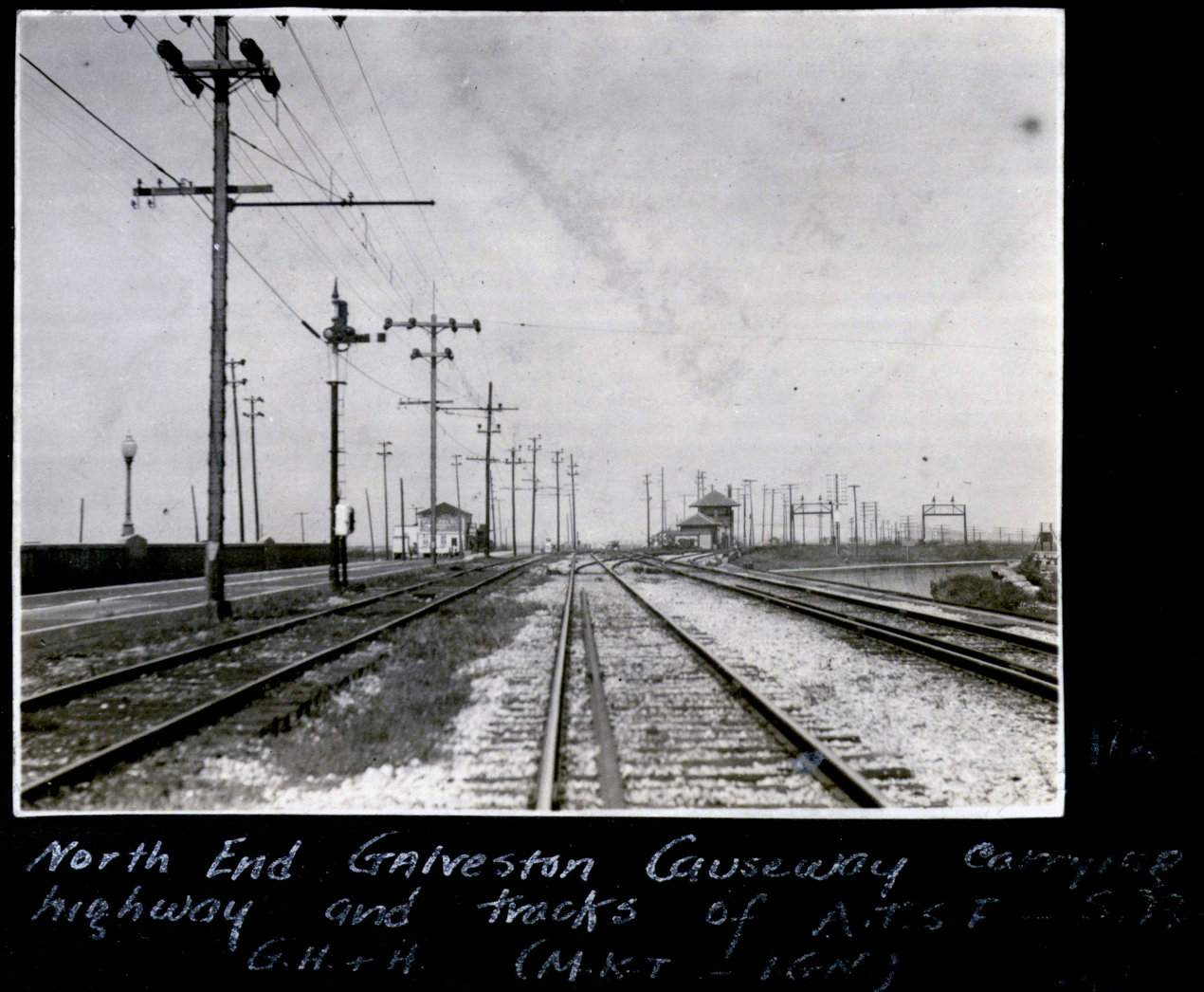

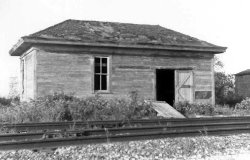

Below: Heading

the opposite direction (toward Galveston Island) on a

different trip, Barriger took this photo as his private railcar passed Tower 98,

the "mainland" tower at Virginia Point. The view is to the northwest and the

track to Barriger's left is the GHE with overhead electrification. The vehicle

roadway is farther left.

Galveston Island was a major port and commercial center in 19th century Texas,

so it is not surprising that railroads sought to provide service to the island.

The first railroad bridge was completed in 1860, owned by the Galveston, Houston

& Henderson (GH&H) Railroad. The GH&H bridge was two miles long,

departing the mainland at Virginia Point. By 1873, it had become apparent to

Galveston civic and commercial leaders that they needed a second railroad onto

the island, preferably one that did not pass through Houston.

For a variety of reasons (including yellow fever

quarantines against Galveston Island), freight bound for

Galveston by way of connection to the GH&H at Houston

did not always reach Galveston. Sometimes it was off-loaded at Houston and

shipped by barge down Buffalo Bayou to Galveston Bay to be loaded directly onto

ships, bypassing the Galveston wharves. To be fair, Houston shippers were trying

to overcome restrictive policies practiced by the Galveston Wharf Company that

favored Galveston's shippers over Houston's.

As S. G. Reed explained in

his reference tome A History of the Texas Railroads

(St. Clair Publishing, 1941), Galveston's citizens were certain that Houston

was...

"...inspired less by fear of the

plague than by a desire to hamper Galveston trade, as the quarantines were

established with regularity every fall when cotton was moving and trade was

best. So the Galveston people in 1873 decided to build a railroad into the

interior which would not pass through Houston."

Galveston's desire to have a railroad that

bypassed Houston led to the founding of the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe (GC&SF)

Railway. With a new bridge over Galveston Bay, Santa Fe construction reached

Arcola in 1877 and Richmond in 1879 (where Santa

Fe founded the adjacent town of Rosenberg.) By 1887, the

GC&SF had become part of the much larger Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe

(AT&SF) Railway,

strengthening Galveston as a major commercial port.

After multiple corporate restructurings, the GH&H

became owned by the Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MK&T, commonly called

"the Katy") Railroad under the control of

rail baron Jay Gould. The Katy did not have tracks as far south as Houston,

so Gould leased the GH&H in 1883 to another railroad he controlled, the International

&

Great Northern (I&GN.) After Gould lost control of the Katy in 1890, the

newly

independent Katy restarted construction to Houston,

arriving in 1895.

The Katy demanded termination of the GH&H lease but the I&GN (still controlled

by the Gould family) refused. After lengthy litigation, the Katy regained

possession of the GH&H but the I&GN was granted permanent and unlimited

trackage rights by the court.

In the 1880s, Southern Pacific (SP) began to expand aggressively into Texas as their line

from California to Houston was completed. A significant part of its construction

was accomplished through arrangements with (and

a financial interest in) the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio (GH&SA) Railway.

The GH&SA ran west from Harrisburg to

San Antonio and beyond, and it was soon acquired

by SP. What SP did not have was a bridge onto

Galveston Island. A third railroad bridge onto the island was not built until

1896, by the Galveston, La Porte and Houston Railway. GH&SA made arrangements to

use the new bridge, but this didn't last long -- the bridge was wiped out by

the massive hurricane of 1900. Only the GC&SF bridge survived that storm and it proved to be a critical

asset in the rebuilding of Galveston.

|

On May 12, 1912, a two-mile reinforced

concrete

causeway opened between Galveston Island and Virginia Point providing two tracks for

steam railroads, a track for the Galveston Houston Electric (GHE) Railway

(an electrified interurban), and a roadway for vehicles. Since the

causeway tracks were shared by multiple railroad companies, interlocking

towers had to be located at each end of the causeway to manage access to

the bridge. And because the causeway was not significantly elevated

above the surface of the waterway, a drawbridge section was incorporated

into the causeway to enable maritime traffic to pass. This required an

additional interlocker on the bridge to manage the controls and approach

signals, and to communicate with maritime traffic regarding the bridge

position. The three towers along the causeway were numbered 96

("Island"), 97 ("Lift Bridge") and 98 ("Virginia Point") by the Railroad

Commission of Texas (RCT.)

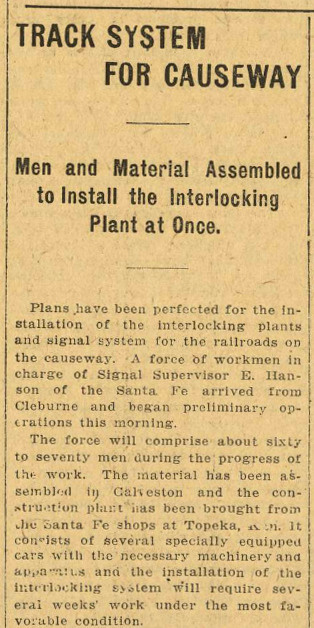

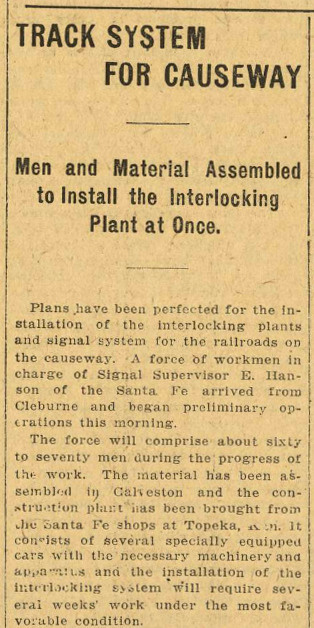

Left: The Galveston

Tribune of March 28, 1912 reported

that the installation of the interlocking plants and associated signals

for the causeway would begin promptly.

Right Top: The

Galveston Tribune of September 13,

1912 noted that RCT Engineer Parker had returned to Austin from

Galveston where he had been

inspecting the causeway's complex interlocking system. Tower 96's

commissioning date, September 6, 1912, suggests that this inspection was

accomplished during Parker's visit. Full operation required all

three towers to be commissioned, which did not occur until mid October.

Right Bottom: The

Galveston Tribune of October

23, 1912 reported that the interlocking system for the entire causeway

became operational earlier that day.

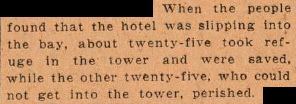

In 1915, another

massive hurricane caused severe damage to the causeway. During the storm, fourteen passengers on a stalled interurban

train escaped to the Causeway Hotel at Virginia Point, joining 36 people

that were already inside. The Galveston Tribune

of August 20, 1915, reported that these 50 people sought final refuge in

Tower 98...

The causeway underwent major repairs with

priority given to restoring rail service, which took about a month.

|

|

The causeway's construction had begun soon after the

contract was awarded on July 5, 1909. A parade celebrating the opening of the

causeway to vehicular traffic was held May 12, 1912. Among the parade entrants

were 23 cars piloted by members of the Houston Automobile Dealers Association,

which anticipated brisk business for new customers able to drive their purchases

home to Galveston.

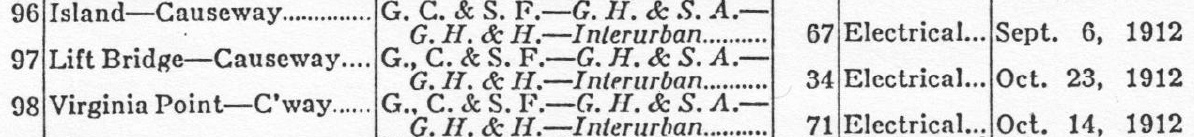

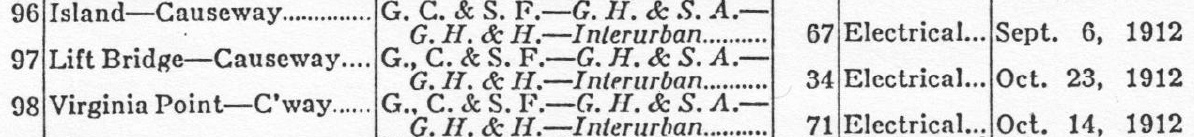

Above: This image snippet from

a table of active interlockers published by RCT

at the end of 1916 shows that the three causeway towers were commissioned in September and October, 1912. They

were each listed with the same four railroads responsible for sharing recurring

operation and maintenance (O&M) expenses. The GC&SF is listed first because it

was the railroad initially responsible for O&M, a duty that periodically rotated

among the steam railroads. [Beginning with the 1916 list, the first named

railroad for each tower was responsible for O&M.] The "Interurban" (GHE) was dropped from the

list beginning with the 1924 RCT Annual Report and there was a corresponding

decrease in the number of functions listed for each of the interlockers. Since

the GHE remained in service until 1936, the reason for this change is unclear.

The list shows Towers 96, 97 and 98 having 67, 34 and 71 functions. Although the towers were

commissioned in the latter part of 1912, they did not appear in RCT's annual

list of active interlockers until the end of 1914.

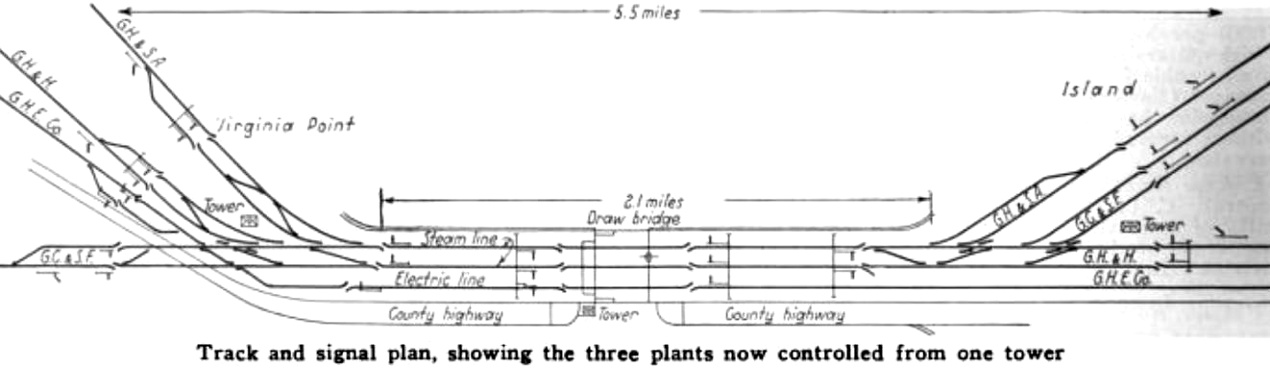

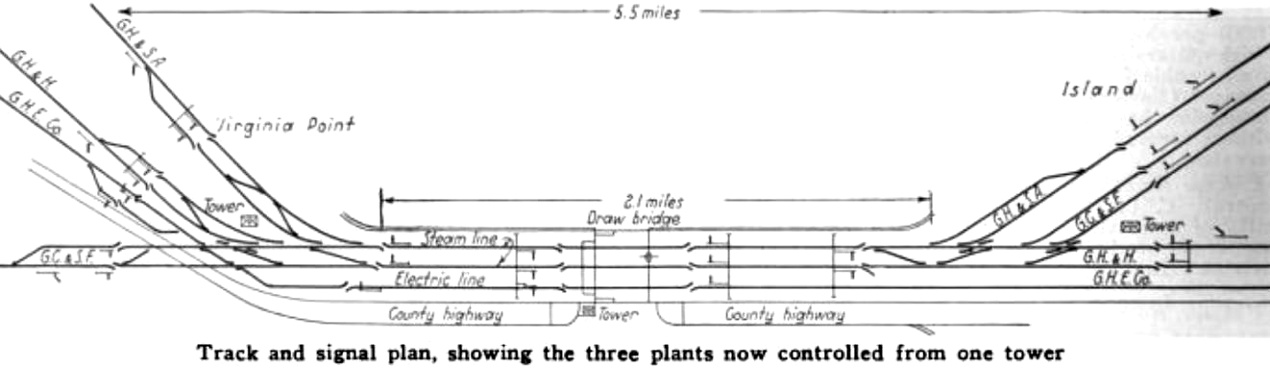

Above: All three towers are

marked (but not labeled) on this graphic, which also identifies the two steam lines

and the single electric line on the Galveston Island Causeway. The tower at the

bridge is Tower 97; Tower

96 (Island) and Tower 98 (Virginia Point) are also depicted. The diagram

appeared in Vol. 21 (1928) of

Railway Signaling and Communications

in an article about the effort to consolidate Towers 96, 97 and 98 into a single

interlocking system. The work was done during a period commencing January, 1927

when Santa Fe was responsible for operating and maintaining the interlockers.

The article noted that these responsibilities rotated among the participating

railroads every five years. As part of its assessment of the feasibility of

consolidation, Santa Fe had determined that on average, the causeway was seeing

50 steam and 45 electric train movements per day, and that a maximum of 75 steam

and 60 electric movements had been observed in a single day.

The span of

interlocking control across the three towers included signals as far as 5.5 miles apart. The

incorporation of train detector circuits was a technology breakthrough that allowed tower operators to control signals

and switches for trains they could not see. This led to the design of an

illuminated track diagram (2 feet high by 23 feet long!) that showed precise

locations of all trains operating within the interlocking boundaries. Choosing to base all of the plants at

Tower 97 minimized the number of wires that needed to be carried in a new

submarine cable under the channel, but it required relocating the Tower 96 and

Tower 98 interlocking plants to Tower 97. All three interlockers used

electro-pneumatic actions to move switches and signals. Since this required

compressed air, Towers 96 and 98 were left in place to house air compressors, relays and other

electronics. The consolidation reduced operating expenses by approximately

$14,000 per year. The article also explains that the existing Tower 97 structure

had to be enlarged to house all of the new equipment.

The railroads that served Galveston were gradually

acquired and merged into larger rail systems. Missouri Pacific (MP) acquired the

I-GN in 1925 and fully merged it in 1956. Union Pacific (UP) acquired MP in 1982

and then acquired the Katy in 1988, merging it into MP. This put the GH&H tracks

completely under MP control. The GH&SA was acquired by SP in the 1880s; in 1934

it was merged into SP's operating railroad for Texas and Louisiana lines, the

Texas & New Orleans (T&NO) Railroad. In 1961, the T&NO was fully merged into SP.

The GC&SF became fully merged into its parent company AT&SF in 1965. In 1995, AT&SF merged with Burlington

Northern to form Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF). The GHE ceased operating

in 1936 and much

of its right-of-way from Houston to Virginia Point now hosts utilities and power lines.

Tower 96 (Island - Causeway)

RCT lists the location of Tower 96 as Island - Causeway. "Island" was the name of

a small community on the peninsula of land between Offatts Bayou and Galveston

Bay. Island had its own school and retained a separate identity until it was

consumed by growth of the City of Galveston. Tower 96 was built on the peninsula

at Island and was the first of the three causeway interlockers authorized for service,

commissioned on September 6, 1912 with a 67-function electrical interlocker. The

1931 RCT Annual Report lists Tower 96 as no

longer in service, reported as "consolidated with No. 97", due to the

1927 interlocking plant relocations.

At the time of its decommissioning, the number of interlocker functions had

dropped to 61.

The Tower 96 structure remained

standing to house air compressors and other electronics for decades. It was abandoned and remained derelict for

many years, but has since been razed.

Above: Two photos of the abandoned Tower 96 showing the north side (left) and northwest

corner (right) of the tower. Note the small phone shanty located behind

(south of) the tower.

(Photos from the Galveston Railroad Museum collection)

Tower 97 (Lift Bridge - Causeway)

Tower 97's location was identified in RCT reports as Lift Bridge - Causeway,

authorized for operation on October 23, 1912 as a 34-function electrical

interlocker. It was the last of the three causeway interlockers to begin

service, located adjacent to the drawbridge span in the middle of the causeway.

It provided the safety system for the bridge by arbitrating access between the

railroads and maritime traffic. The original Tower 97 structure was replaced with a modern building to control the drawbridge, signal lights and

switches on both approaches. As discussed above, the Tower 96 and 98

interlockers were relocated to Tower 97 in 1928 which required expanding the

upper floor of the facility. The retirement of Tower 17

in Rosenberg in 2004 left Tower 97 as the last manned interlocking tower in Texas.

The original lift bridge was replaced in 1987 with a bascule bridge that

pivoted from the island side, not the mainland side as the original had. To widen the waterway, the causeway needed to be shortened from the

middle; this was easier to accomplish by removing a portion of the causeway

on the island side since it did not have the existing bridge pivot assembly and

tower structures that sat on the mainland side. In 2012, the 1987 bascule bridge was replaced by a much longer

vertical lift bridge to satisfy Coast Guard

Intra-Coastal Waterway safety requirements. Stuart L. Schroeder reports...

"At the time of my retirement in November 2016, there was still an operator

at the Galveston lift bridge but the BNSF Galveston Subdivision train

dispatcher in Spring had a role in the operation of the bridge." There

is only one railroad track across the causeway, but the timing of when the other

tracks were removed is undetermined.

Above Left: This Library of

Congress photo was possibly taken at the commissioning of Tower 97. With boats,

rail cars and automobiles, something special appears to be happening. At the

time, the upper floor of the Tower 97

building housed the tower structure and nothing else. Note that the counterweight of the drawbridge

is adjacent to the tower, which is on the mainland side of the waterway. This

changed when the drawbridge was replaced.

Above Center: Don Harper took this photo that shows both Tower 97 structures: the original

(left) and the new one (right). The original building had been modified so that the upper floor

occupied the full extent of the building. This was accomplished during the 1928

consolidation of all three interlocking machines into Tower 97 so that Towers 96

and 98 were no longer manned. The new tower building was constructed when the

drawbridge was replaced by a larger bascule bridge in 1987. Like the prior

bridge, the counterweight of the new bridge is adjacent to the tower, but both

are now on the island side of the waterway.

Above Right: Daniel Walford

took this close-up of the abandoned structure.

Above: The Galveston tourism

bureau wanted to make sure visitors knew they were welcome in Galveston! Note

that the vehicle approaching the camera has been routed onto the GHE tracks. The

roadway was on the other side of the wall at right, so vehciles had to go around Tower 97

by briefly driving on pavement in which the GHE tracks were embedded. (Galveston Historical Foundation photo)

On 9/3/2002, Don Harper emailed

a description of a visit he made to Tower 97:

"I watched while signals and switches were aligned several times.

All pushbutton operation. ... The tower is noisy. There are at least 3 radios in there, one

BNSF, one UP, and one on channel 16 for boat traffic. The operator

was kept hopping much of the time I was there. Several vessels

passed through, the Gulfliner went through 3 times and a BNSF

outbound passed by. ... An interesting sideline: the tower operator records the names

of tow boats passing the tower, what their load is, and the direction

they are heading ... at the request of the Coast Guard. If a

vessel is reported missing or sinking, the Coast Guard has a general frame

of reference as to where the vessel might be."

1981 Barge Collision

In a Railspot post dated February

22, 2017, Rollin Bredenberg recounted this story...

"SP operated the bridge until the infamous incident in

1981 when the SP operator told a northbound tow of barges to proceed into the

old bascule structure. The tow boat captain was running in dense fog and asked

her if the bridge was open. She said "no, but I'll raise it up for you." Turns

out she had been doing a good bit of weed smoking that night, and instead of

raising the bridge she went downstairs to the rest room. When the captain saw

that the bridge was still down (10 min. after the initial radio conversation) he

immediately sounded his horn in short rapid bursts, at which point the 24 year

old SP operator ran as fast as she could away from the control house. The

inevitable collision compromised the barges causing the butadiene to bleed.

After the initial explosions the product burned for over a day. The bascule

span was useless scrap metal. The incident did not affect SP greatly except for sulphur trains that could not get onto the island. ATSF, on the other hand, was

severely impacted and incensed that they were separated from the island for IIRC

three weeks. ATSF asked that SP allow ATSF to take over control and maintenance

of the bridge. SP gladly agreed and that is why BNSF now controls the bridge.

There were no injuries resulting from this accident. The operator did not show

up for her formal investigation and her short railroad career ended that night."

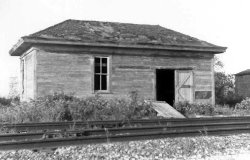

Tower 98 (Virginia Point - Causeway)

Tower 98 was a 71-function electric-pneumatic interlocker located at Virginia

Point on the mainland end of the causeway. It was commissioned for operation on

October 14, 1912 and decommissioned in 1928 when its interlocking plant was

relocated to Tower 97. Virginia Point dates back to at least 1840 when a

community was organized at the site of a ferry operation. Virginia Point was

intended to become the founding site of Texas City, but that town was laid out

farther north after the hurricane of 1900. Virginia Point expanded as a result

of the completion of the new causeway in 1912, but the community was wiped out

again by a major hurricane in 1915. Some portions of the community were rebuilt,

but it remained underdeveloped and was annexed by Texas City in 1952. Despite

decommissioning in 1929, Tower 98 remained intact to house air compressors and

other electronics for the consolidated interlocking system. It eventually was

abandoned and remained standing into the 1980s.

|

Left:

Northwest corner of Tower 98 (Galveston Railroad Museum collection)

Right: Southwest

corner of Tower 98 (Tom Kline, 1978) |

|

A highway bridge built onto the island in 1938 carried lanes in both

directions and incorporated a drawbridge. This allowed vehicular traffic to be

removed from the 1912 causeway. By the mid-1950s, the 1938 bridge was inadequate

for the higher traffic levels being experienced, so a new bridge was built that was high enough to not

require a drawbridge. Traffic was relocated to this new bridge in 1961 while the

old bridge was substantially modified to raise its height so that its drawbridge

could be eliminated. When it reopened in 1964, the two bridges were used to

carry traffic in opposite directions. In 2003, construction began on new bridges for Interstate 45 traffic to replace the older ones. The new

northbound bridge opened in 2005; the southbound bridge opened in 2008. This new

I-45 causeway was rededicated as the George and Cynthia Mitchell

Memorial Causeway in 2016.

Additional Tower 97 and Causeway Photos by Don Harper (click to enlarge)

lift bridge counter-weight |

old

(left) and new (right) towers |

plant

panel and bridge controls plant

panel and bridge controls |

interior view |

causeway, November 1957 |

Gulfliner northbound |

Gulfliner southbound past old tower |

merging onto causeway (cab view) |

lift bridge approach (cab view) |

|

Images from the Post Card Collection of

Bruce Blalock (click to enlarge)

Additional Photos of Tower 96 (click to enlarge)

Bob Nicholson, Sept 1970 |

Carl Codney

collection, undated |

Ralph Back, Nov. 14, 1971 |

east

side, Galveston RR Museum coll. |

north side, Galveston RR Museum coll. |

Additional Tower 98 Photos from the Galveston

Railroad Museum (click to enlarge)

east side |

southwest corner |

west side |

interior |

Additional Photos of Tower 98 from the Tom Kline collection (click to

enlarge)

GC&SF/GH&H split |

west approach |

east approach |

north side |

Additional Photos of Tower 98 by Mark Nerren in 1980

(click to enlarge)

west side |

northeast corner |

section house |

Images from the Steven M. Baron Collection (click to

enlarge)

Interurban crossing lift

bridge |

Interurban viaduct |

Interurban on causeway |

Tower 98 after the Hurricane of 1915 |

magnified view |

Above: The span of the 1987

bascule bridge limited maritime traffic to less than 100 ft. width, a problem

that the U.S. Coast Guard had long identified. In the early 2000s, planning for

a new vertical lift bridge to replace the bascule bridge was undertaken to

triple the width of the passageway. The new bridge was installed in 2012. The

freeway visible in the upper part of these photos is the Interstate 45 causeway

that opened in 2005-2008. (photos provided by Brasfield & Gorrie)

Brasfield & Gorrie is a construction company that led a

joint venture team to build and install the new vertical lift bridge. They

explain that the ...

"...bridge is a 382-foot main lift

span that rises 80 feet to allow Intercoastal waterway traffic on Galveston Bay

to pass under the BNSF Railroad. ... Challenges of this project included the

placement of all of the mass concrete for the tower foundations. Each pier has

approximately 5,000 cubic yards of concrete that were placed in varying lifts,

ranging from 700 to 1,300 cubic yards. ... Perhaps the biggest challenge was the

float-out of the old bascule bridge and float-in of the main span. This

float-out/float-in procedure had to be completed within a 72-hour marine channel

shutdown, with only a 12-hour window to close the bridge from rail traffic. The

main span was built at the port, placed on barges, and then floated into place,

with only eight inches of clearance between the towers and new span.